Key Takeaways

- Tumor size, stage, and grade directly shape which therapies are viable.

- Early‑stage tumours often qualify for surgery alone, while larger or metastatic tumours need systemic treatments.

- Radiation works best when the tumour is localized and still growing slowly.

- Chemo, immunotherapy, and targeted drugs are chosen based on how fast the tumour spreads and its molecular profile.

- A multidisciplinary team tailors the plan, balancing cure chances with side‑effects.

Understanding tumor growth is the first step in figuring out why some patients get surgery while others end up on a cocktail of drugs. Below we break down the biology, the staging jargon, and how every piece nudges doctors toward a specific treatment path.

What Is Tumor Growth?

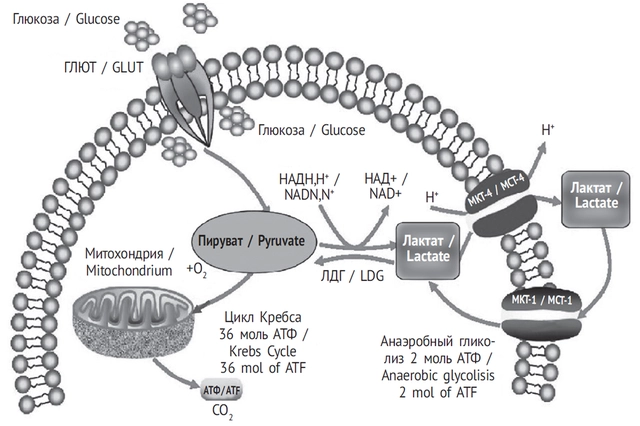

Tumor growth is the process by which abnormal cells divide, enlarge, and sometimes invade nearby tissues. In simple terms, it’s how a lump of cancer cells gets bigger over time. The speed of that growth-measured in weeks, months, or even days-tells oncologists whether the cancer is aggressive or indolent. Faster growth usually means the tumour is more likely to spread and harder to control with local therapies alone.

Why Size, Stage, and Grade Matter

Tumor stage is a classification that describes how far the cancer has spread within the body, based on size, depth, and involvement of nearby structures. Staging uses the TNM system (Tumour, Nodes, Metastasis) and ranges from Stage I (small, localized) to Stage IV (widely metastatic). Tumor grade is an assessment of how abnormal the cancer cells look under a microscope, indicating how quickly they are likely to grow. Low‑grade tumours look more like normal tissue and tend to grow slowly; high‑grade tumours are chaotic and aggressive.

Both stage and grade act like a traffic light for treatment: early stage + low grade often means surgery can remove the whole tumour, while advanced stage + high grade pushes doctors toward systemic options.

Metastasis: When Cancer Spreads

Metastasis is the process by which cancer cells break away from the primary tumour, travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and form new tumours in distant organs. Once metastasis occurs, local treatments like surgery lose their curative punch because the disease is no longer confined. Instead, therapies that travel throughout the body-chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted drugs-become essential.

Surgery: Removing What You Can See

Surgery is a physical procedure that cuts out the tumour and a margin of healthy tissue, aiming for complete removal. It works best for tumours that are small, well‑defined, and haven’t invaded critical structures. If imaging shows a tumour under 2cm and no nodal involvement, surgeons may aim for a “wide local excision” that can be curative.

But when the tumour has grown into surrounding vessels or bones, surgery becomes risky. In those cases, doctors might combine a limited operation with radiation or chemo to mop up hidden cells.

Radiation Therapy: Targeting Growing Cells

Radiation therapy is the use of high‑energy beams (like X‑rays) to damage cancer DNA, thwarting cell division. Radiation thrives when the tumour is localized and still proliferating. A rapidly expanding tumour will absorb more radiation dose, but too fast a growth can outpace the treatment, requiring higher doses or a combination with chemo (called chemoradiation).

For head‑and‑neck cancers, for instance, doctors often give a 70Gy dose over seven weeks, timing it to the tumour’s growth curve to maximize DNA damage while sparing healthy tissue.

Chemotherapy & Immunotherapy: Systemic Strategies

Chemotherapy is a class of drugs that travel through the bloodstream to kill rapidly dividing cells throughout the body. It’s the go‑to when tumours are large, high‑grade, or have metastasized. Regimens like paclitaxel or doxorubicin are chosen based on the tumour’s origin and growth rate.

Immunotherapy is a treatment that empowers the patient’s own immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., pembrolizumab) work best on tumours that show high mutational burden-a sign of fast‑growing, genetically unstable cancer. When the tumour’s growth creates many new antigens, the immune system gets more “flags” to target.

Often, doctors pair chemo with immunotherapy to both shrink the tumour and expose it to immune attack.

Emerging Options: Targeted Therapy & Biomarkers

Targeted drugs home in on specific molecular drivers (like EGFR or HER2) that fuel tumour growth. If a biopsy reveals a mutation, a pill such as osimertinib can halt growth without the broad toxicity of chemo.

Biomarker testing has become a routine part of staging. It tells clinicians whether a tumour’s rapid growth is driven by a particular pathway, opening the door to personalised pills that essentially “turn off” the growth engine.

Decision‑Making Checklist

- Is the tumour localized (Stage I‑II) or has it spread (Stage III‑IV)?

- What is the grade? Low‑grade = slower growth, high‑grade = aggressive.

- Has metastasis been detected?

- Are there actionable mutations or biomarkers?

- What is the patient’s performance status and comorbidities?

- Do we aim for cure, control, or palliation?

Answering these questions helps the multidisciplinary team map out a treatment road that aligns with how fast the tumour is growing and where it’s headed.

Comparison of Common Treatment Choices

| Treatment | Best For (Stage/Size) | Key Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Stage I‑II, ≤3cm, no invasion | Potential cure, immediate removal | Not feasible if tumour encroaches vital structures |

| Radiation | Localized, moderate growth rate | Preserves organ, can shrink before surgery | Skin/organ toxicity, limited for large metastases |

| Chemotherapy | Stage III‑IV, high‑grade, metastatic | Systemic reach, works on fast‑growing cells | Side‑effects, resistance over time |

| Immunotherapy | High mutational burden, checkpoint‑positive tumours | Durable responses, less DNA damage | Only works for certain tumour types, immune‑related AEs |

| Targeted Therapy | Biomarker‑positive, any stage | Precision, fewer off‑target effects | Requires mutation, resistance can develop |

Frequently Asked Questions

How does tumour size influence the choice of surgery?

Smaller tumours (usually <2cm) can be removed with clear margins, giving a higher chance of cure. Larger tumours may need a combination of surgery and other treatments to address microscopic spread.

When is radiation preferred over chemotherapy?

Radiation shines when the cancer is confined to a specific area and the growth rate allows a full dose to be delivered. Chemotherapy is chosen when the disease has spread beyond the radiation field.

Can fast‑growing tumours become resistant to chemo?

Yes. Rapidly dividing cells can acquire mutations that pump out the drug or repair DNA damage more efficiently, so oncologists may switch families of chemo or add targeted agents.

What role do biomarkers play in treatment decisions?

Biomarkers tell doctors which molecular pathways are driving the tumour’s growth. If a mutation is found, a targeted drug can shut down that pathway, often with fewer side‑effects than standard chemo.

Is immunotherapy effective for all cancer types?

Not yet. It works best for tumours that show high mutational load or express checkpoint proteins. Lung, melanoma, and kidney cancers have responded well; others still need more research.

11 Comments

Jesse Najarro

Great overview, really helps understand why size matters in choosing treatment

Dan Dawson

Nice read I like how you broke down the stages

I think it makes it easier for patients to follow

Robert Frith

Wow man this is like a warzone inside the body!! Tumours grow rn and doctors gotta pick the right weapons!!! It’s all about size and speed-big bads need chemo, tiny ones get sliced!!

Albert Gesierich

In reviewing the presented material one must first acknowledge the precision with which tumor staging is delineated. The TNM classification system, while ostensibly straightforward, encapsulates a wealth of prognostic information. Accurate measurement of tumor dimensions directly influences surgical eligibility. Likewise, nodal involvement dictates the necessity for adjuvant therapy. Histologic grade, as assessed by cellular differentiation, provides insight into proliferative kinetics. High‑grade lesions invariably exhibit accelerated growth curves, thereby limiting the efficacy of localized modalities. Molecular profiling, when incorporated, refines therapeutic selection by identifying actionable mutations. Biomarker assessment should not be relegated to an ancillary role; it is integral to personalized medicine. Moreover, the timing of radiation relative to chemotherapeutic cycles can significantly affect tumor radiosensitivity. Clinical trials have demonstrated that concurrent chemoradiation improves local control in certain head‑and‑neck cancers. It is essential, however, to balance curative intent against potential toxicity. Patient performance status remains a pivotal factor in determining tolerance to systemic regimens. Multidisciplinary discussion ensures that each facet of tumor biology is considered in the treatment algorithm. Finally, ongoing surveillance post‑therapy is required to detect recurrence at the earliest possible stage. In summary, the interplay between tumor growth dynamics and treatment selection is complex and demands a nuanced, evidence‑based approach.

Brad Tollefson

Thanks for the thorough breakdown Albert. Your point about biomarker testing is spot‑on. I’d just add that the timing of radiation can be crucial, especially in head‑and‑neck cases. Apologize for any typo – the word “crutial” was miss‑spelt earlier.

Paul van de Runstraat

Oh sure, because everybody loves reading a table of treatment options while they’re waiting for chemo, right?

Angelo Truglio

Let’s be clear!!! Tumor growth isn’t some gentle garden weed!!! It’s a ruthless beast, demanding aggressive action!!! 🤬

Sarah Aderholdt

Growth defines destiny; size defines choice.

Phoebe Chico

Yo, that line hits deep! It’s like the tumor’s hustle mirrors life’s grind-only the bold survive, you feel me?

Larry Douglas

In oncologic practice the correlation between proliferative index and therapeutic modality is well documented

Ann Campanella

This article drags on way too much.