When antibiotics run out, people don’t just wait longer for their medicine-they risk dying from infections that should be easy to treat. In 2023, one in six bacterial infections worldwide didn’t respond to standard antibiotics. For urinary tract infections, that number jumped to one in three. And now, with critical shortages of common drugs like penicillin, amoxicillin, and cephalosporins, doctors are being forced to make impossible choices: use a toxic last-resort drug, delay treatment, or send a patient home with no options at all.

Why Antibiotics Are More Likely to Run Out Than Other Drugs

Antibiotics are 42% more likely to face shortages than any other type of medication. Why? It’s not because they’re hard to make-it’s because no one wants to make them. Generic antibiotics, which make up 85% of global use, sell for pennies. A single dose of amoxicillin might cost less than 10 cents. But producing sterile injectables requires clean rooms, strict quality controls, and trained staff-all expensive. Meanwhile, regulatory costs have gone up 34% since 2015. Manufacturers don’t see a return on that investment. So they shift production to more profitable drugs: cancer treatments, diabetes meds, painkillers. Antibiotics? They’re treated like commodities, not life-saving tools.The Global Picture: Who’s Getting Hit Hardest

The U.S. hit a 10-year high for drug shortages in 2024, with 147 active antibiotic shortages listed by the FDA. But it’s not just America. The European Economic Area reported 28 countries facing shortages, 14 of them calling it a critical crisis. In the UK, Brexit pushed antibiotic shortages from 648 in 2020 to 1,634 in 2023. Meanwhile, low- and middle-income countries are in even worse shape. In parts of Africa and South Asia, 70% of antibiotics are already inaccessible. A nurse in rural Kenya told the WHO: “When penicillin isn’t available, we send patients home. We know they might die.”What Happens When the Medicine Isn’t There

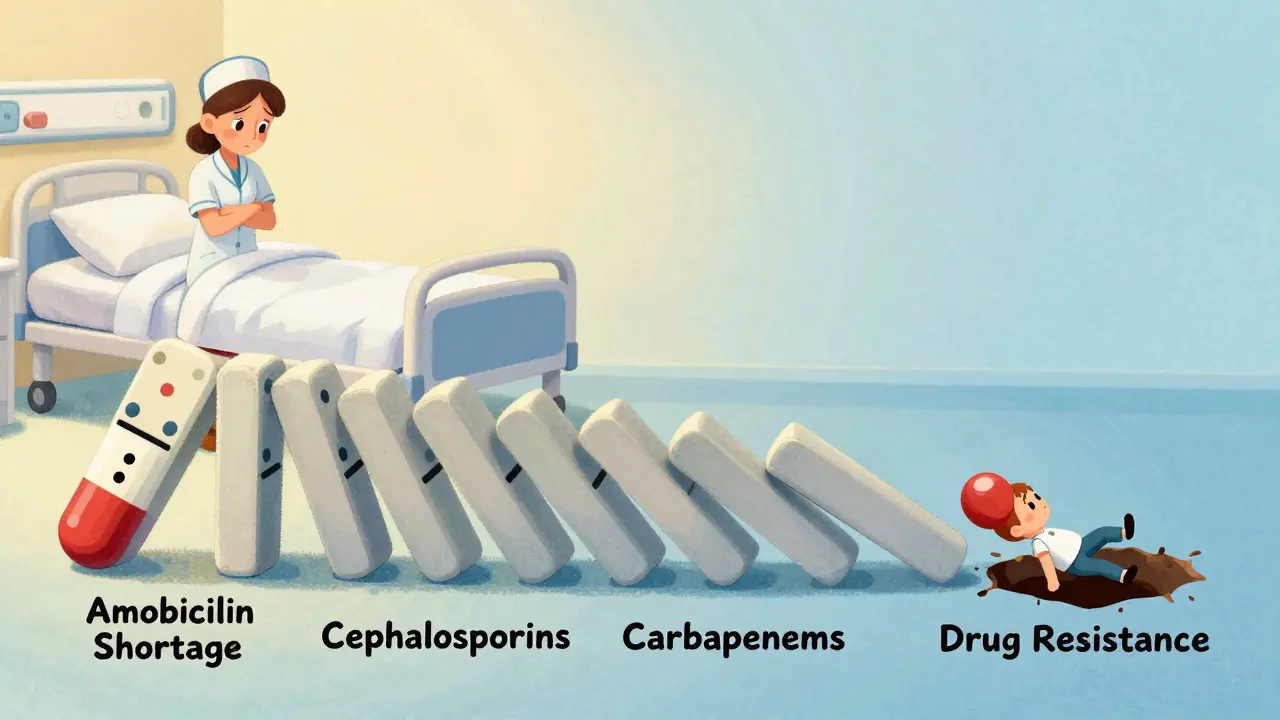

When amoxicillin runs out, doctors turn to broader-spectrum antibiotics like carbapenems. That’s a problem. Carbapenems are powerful, last-line drugs. Using them for routine infections speeds up resistance. By 2023, over 40% of E. coli and 55% of K. pneumoniae were already resistant to third-generation cephalosporins. When those fail, carbapenems become the only option. But overuse makes them fail too. It’s a domino effect. In the U.S., 78% of hospital pharmacists say they’ve had to change treatment plans because of shortages. Sixty-two percent report more patients developing complications. One doctor in California told the APHA forum she had to use colistin-a drug so toxic it causes kidney failure-for a simple UTI. Another in the UK said they’re rationing amoxicillin. In Mumbai, a child’s pneumonia treatment was delayed 72 hours because azithromycin wasn’t available. By the time she got it, she needed ICU care.

The Economic Trap: Why Companies Won’t Make More

The global antibiotic market was worth $38.7 billion in 2024. Sounds big, right? But it grew just 1.2% from 2019 to 2024. Compare that to the rest of the pharmaceutical industry, which grew 5.7%. Why the gap? Because antibiotics are cheap. Prices have dropped 27% since 2015, mostly due to competition from manufacturers in India and China. Even when demand spikes-like during a flu season or a pandemic-companies don’t ramp up production. Why? Because they can’t make enough profit to justify the cost. And if a factory shuts down for compliance issues? That’s it. No backup. No buffer. Just empty shelves.What’s Being Done-and Why It’s Not Enough

The WHO announced a five-point plan in October 2025, including a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing facilities in January 2025, expected to ease 15% of shortages by late 2025. The European Commission is pushing its Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe, aiming to fix supply chains by 2026. But these are long-term fixes. The problem is happening now. Some hospitals are getting smarter. Johns Hopkins implemented rapid diagnostic tests during shortages. That cut unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 37%. California created a regional sharing network that reduced critical shortages by 43% across 12 hospitals. But these are exceptions. Most hospitals still struggle. Only 37% of U.S. antimicrobial stewardship programs meet WHO standards. And in places without labs, without pharmacists, without funding? There’s no plan at all.

The Human Cost: Real Stories Behind the Numbers

Behind every statistic is a person. A baby in Nairobi who can’t get penicillin for pneumonia. A diabetic in Detroit whose foot ulcer turns septic because ciprofloxacin is out of stock. A grandmother in Spain who waits three weeks for a replacement dose of amoxicillin-clavulanate, her infection worsening each day. These aren’t hypotheticals. They’re happening in cities and villages, in rich countries and poor ones, every single day.What You Can Do-And What Needs to Change

As a patient, you can’t fix the supply chain. But you can ask questions. If your doctor prescribes an antibiotic, ask: “Is this the right one? Is there an alternative if this runs out?” Don’t pressure your doctor for antibiotics when you have a virus. Every unnecessary prescription adds pressure to the system. Support policies that fund antibiotic production, not just research. Push for public investment in manufacturing. Right now, the market fails us. It’s not about profit-it’s about survival.What’s Next?

Without major changes, antibiotic shortages will grow by 40% by 2030. The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance predicts 1.2 million extra deaths each year from infections we used to cure. The WHO wants 70% of antibiotic use to come from safe, accessible drugs by 2030. Right now, it’s 58%. We’re falling behind. The tools to fix this exist: better diagnostics, smarter prescribing, fairer pricing, and public investment. But time is running out. The next infection that doesn’t respond to treatment might not be someone else’s. It might be yours.Why are antibiotics running out when we need them more than ever?

Antibiotics are cheap to produce but expensive to make safely. Manufacturers avoid them because profit margins are too low. Generic antibiotics sell for pennies per dose, while regulatory and production costs have risen sharply. Companies focus on more profitable drugs like cancer treatments or diabetes meds, leaving antibiotics underproduced-even as resistance grows.

Are there alternatives when my antibiotic is out of stock?

Sometimes, but rarely. Unlike other drugs, antibiotics often have no equally effective substitutes, especially for resistant infections. For example, if amoxicillin is unavailable, doctors might switch to a broader-spectrum drug like amoxicillin-clavulanate or even carbapenems. But these drugs are stronger, more toxic, and speed up resistance. In low-resource areas, there may be no alternative at all.

Which antibiotics are in shortest supply right now?

Penicillin G benzathine has been in short supply since 2015 due to manufacturing issues and low profitability. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin-clavulanate faced major shortages in 2023, leading to a 55% and 69% drop in use across Europe. Third-generation cephalosporins are also scarce in many regions, forcing doctors to rely on last-resort drugs like carbapenems. The U.S. FDA listed 147 active antibiotic shortages as of December 2024.

How do antibiotic shortages affect antibiotic resistance?

Shortages force doctors to use broader-spectrum antibiotics when first-line drugs aren’t available. These drugs kill more types of bacteria, increasing pressure on microbes to evolve resistance. For example, when cephalosporins run out, carbapenems get overused. That’s how resistant strains like MRSA and CRE spread faster. Shortages and resistance are linked in a dangerous cycle: fewer options lead to worse resistance, which leads to even fewer options.

Can importing antibiotics solve the problem?

It helps in wealthy countries, but it’s not a real solution. The U.S. and EU rely on imports from India and China, but those countries face their own regulatory and supply issues. A factory shutdown in one country can ripple globally. Low- and middle-income countries often can’t afford imports at all. Plus, global supply chains are fragile-geopolitical events like Brexit or trade disputes can cut off access overnight.

What’s being done to fix antibiotic shortages?

The WHO launched a $500 million Global Antibiotic Supply Security Initiative in 2025. The U.S. FDA approved two new manufacturing facilities expected to ease 15% of shortages by late 2025. The European Commission is updating regulations to incentivize production. Hospitals are using antimicrobial stewardship programs to reduce waste. But these efforts are slow. Manufacturing infrastructure hasn’t kept up with demand, and without guaranteed profits, companies still won’t invest.

10 Comments

James Rayner

It’s heartbreaking… really. I mean, we’ve got people dying because a pill costs less than a coffee, and the system just… shrugs? 🤷♂️💔 I keep thinking about my grandma who survived pneumonia in the ‘70s with penicillin-and now, if she got it today, they might not even have it on the shelf. How did we get here? We’re not just failing healthcare-we’re failing humanity.

Souhardya Paul

There’s a reason why this isn’t getting fixed-it’s not a medical problem, it’s an economic one. We treat antibiotics like toilet paper instead of life support. Companies aren’t evil, they’re just following the math. But we built a system where profit overrides survival. Someone’s gotta pay to make these drugs, and right now, the market says ‘no.’ We need public manufacturing. Like, actual government-run antibiotic factories. Not just ‘incentives.’ Real investment.

Josias Ariel Mahlangu

This is what happens when you let capitalism run wild. In Africa, we’ve been dealing with this for decades. No one cares until it’s a rich white kid in Ohio who can’t get amoxicillin. Meanwhile, kids in Lagos are just… gone. And now the West is acting shocked? Wake up. This wasn’t an accident. It was a choice.

Dan Padgett

Man, it’s like we’ve got a fire in the basement and everyone’s忙着给客厅的沙发换新罩子. We got all these fancy new cancer drugs, fancy diabetes gadgets, fancy painkillers with TikTok ads-but the thing that keeps you alive after a scraped knee? Gone. And nobody’s even mad. Just… shrugs. Like, ‘oh well, maybe next year.’ But next year, the infection doesn’t wait. It multiplies. It wins. And then it’s too late.

Joanna Ebizie

Ugh. Of course this is happening. Who even makes antibiotics anymore? Oh right-some sketchy factory in India that got caught falsifying data last year. And now we’re supposed to trust them? I don’t care how cheap it is-if it’s not made in America, it’s a gamble. And now people are dying because we outsourced our survival? Classic.

Dylan Smith

Stop pretending this is about profit. It’s about power. The same people who own the drug companies own the FDA, the WHO, the Congress. They don’t want antibiotics to be cheap and accessible. They want you dependent on their expensive last-resort drugs. This is a controlled collapse. They’re letting the system break so they can sell you the ‘solution’ later at 10x the price. Watch.

Kitty Price

Just read this and cried in my coffee ☕️ I’ve had three UTIs in the last year. Each time, my doctor just said ‘try this.’ I never thought about how hard it might be to get. I’m so grateful I live where I do. But I never realized how fragile it all is. Thank you for writing this. It’s terrifying… but important.

Aditya Kumar

Idk man. I just take the pill when I get sick. If it’s out, I guess I’ll just wait. Probably fine.

Colleen Bigelow

This is what happens when you let illegal immigrants and foreign drug cartels take over our medicine supply. The FDA approves factories in India that don’t even meet basic hygiene standards. And now our kids are dying because we let the world make our pills? We need a border wall around pharmaceuticals. No more imports. Make it here. Or don’t make it at all.

Randolph Rickman

There’s hope. Look at Johns Hopkins-they cut unnecessary antibiotic use by 37% with smart diagnostics. California’s sharing network cut shortages by 43%. We don’t need magic. We need coordination. We need hospitals to talk to each other. We need pharmacists trained to spot resistance early. We need policymakers to fund this like it’s a national security crisis-because it is. This isn’t about money. It’s about will. And we’ve got the will. We just need to use it.