Introduction to Sarcoptes scabiei: The Invisible Enemy

As someone who's always been fascinated by the world of microscopic organisms, I was drawn to explore the life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei, a microscopic mite responsible for the skin condition known as scabies. In this article, I will delve into the life cycle of these tiny parasites and examine their impact on human health. By understanding the biology of Sarcoptes scabiei, we can raise awareness of the importance of prevention and treatment of scabies, as well as equip ourselves with the knowledge to combat this persistent and highly contagious skin disease.

Understanding the Life Cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei

The life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei is divided into four main stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. It all begins with the adult female mite, which burrows into the upper layer of the human skin and lays eggs. Within 3 to 4 days, these eggs hatch into larvae, which then migrate to the skin surface. The larval stage lasts for about 3 to 4 days, after which the larvae molt into nymphs. Nymphs go through two stages – protonymph and tritonymph – before becoming adult mites. The entire life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei takes approximately 10 to 17 days to complete.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Scabies

Scabies is an itchy skin condition caused by the infestation of Sarcoptes scabiei mites. The primary symptom of scabies is intense itching, which is often worse at night. This itching, in turn, leads to scratching, which can cause skin abrasions and secondary bacterial infections. Scabies is also characterized by a skin rash consisting of tiny red bumps and blisters. The rash usually appears in areas where the mites have burrowed, such as between the fingers, on the wrists, in the armpits, around the waist, and on the genitals.

How Sarcoptes scabiei Spreads

One of the reasons why scabies is such a prevalent and difficult-to-eradicate disease is the ease with which Sarcoptes scabiei can spread from person to person. The primary mode of transmission is through direct skin-to-skin contact, which is why scabies outbreaks are common in crowded settings such as schools, nursing homes, and prisons. Indirect transmission can also occur through contact with contaminated clothing, bedding, or towels. Since the mites can survive for up to 72 hours away from human skin, it's essential to practice good hygiene and wash any potentially contaminated items to prevent the spread of scabies.

Diagnosing and Treating Scabies

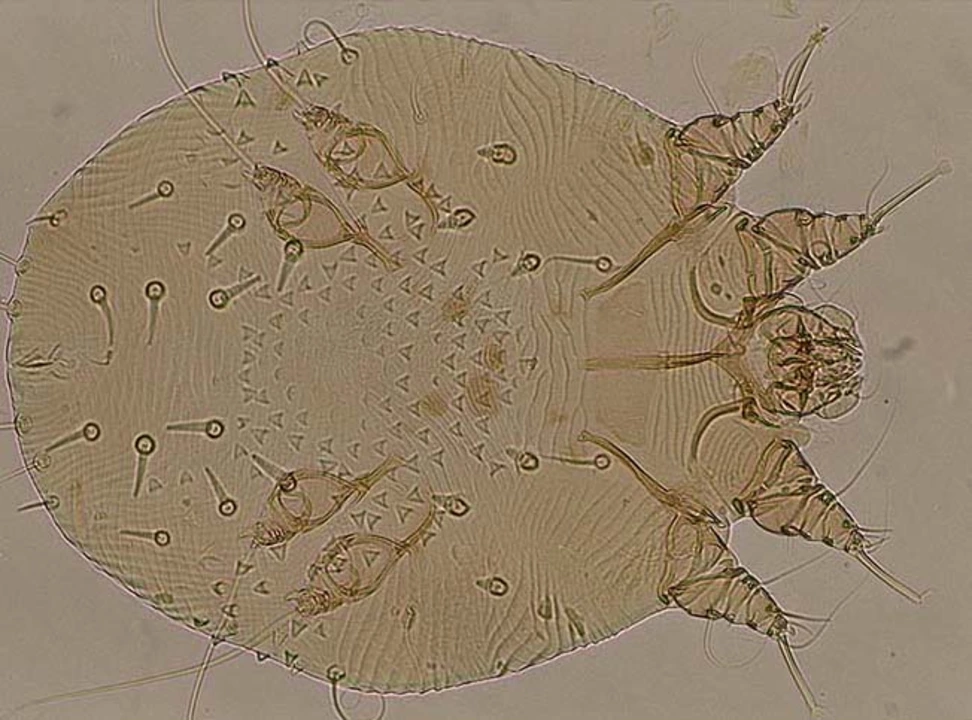

Diagnosing scabies can be challenging due to the small size of the mites and the similarity of its symptoms to other skin conditions. A definitive diagnosis is usually made by examining skin scrapings under a microscope to identify the presence of mites, eggs, or fecal pellets. Once diagnosed, scabies can be effectively treated with prescription medications called scabicides, which are applied topically to the entire body. It's important to follow the doctor's instructions and complete the full course of treatment to ensure the eradication of all mites and prevent reinfection.

Preventing Scabies: Tips for Staying Mite-Free

Preventing scabies begins with practicing good personal hygiene and avoiding close contact with individuals who have been diagnosed with the condition. Regular handwashing, showering, and laundering of clothing, bedding, and towels can help minimize the risk of contracting scabies. In cases where a family member or close contact has been diagnosed with scabies, it's important to treat all household members and wash all potentially contaminated items in hot water and high heat to kill any lingering mites.

Conclusion: The Importance of Awareness and Action

While Sarcoptes scabiei may be tiny, its impact on human health can be significant. By understanding the life cycle of these mites and being aware of the symptoms, transmission, and treatment of scabies, we can take steps to prevent the spread of this highly contagious skin condition. Let's work together to raise awareness about scabies, promote good hygiene practices, and support those affected by this persistent and often stigmatized disease.

10 Comments

Calandra Harris

Scabies is a textbook example of how foreign parasites exploit weak public health systems and anyone who ignores basic hygiene is complicit

Dan Burbank

Oh dear, the mere mention of Sarcoptes scabiei conjures images of a microscopic apocalypse that swarms our very skin! The author tries to simplify a complex life cycle, yet fails to capture the theatrical drama of each mite’s clandestine journey. One can almost hear the faint moan of the larvae as they crawl to the surface, a silent chorus of suffering. Truly, this article glosses over the profound existential crisis these parasites impose on humanity.

Anna Marie

Appreciate the thorough overview, especially the practical tips on laundering and treating household members. It’s crucial that we all stay vigilant and share reliable information rather than spread myths. For anyone dealing with an outbreak, following a dermatologist’s regimen is the safest path forward.

Abdulraheem yahya

While I admire the enthusiasm for public health, the dramatization can obscure the simple truth: prevention is a collective effort. Regular hand‑washing and immediate treatment of contacts break the transmission chain. Moreover, respecting cultural practices in communal settings, like locker rooms, can reduce stigma. Let’s not forget that the mites’ survival off‑host is limited, so quick environmental decontamination works wonders.

In short, a balanced approach of hygiene, education, and timely medical care is the optimal strategy.

Preeti Sharma

Interesting summary, yet one could argue that the focus on individual hygiene overlooks systemic issues such as overcrowded housing and inadequate healthcare access. Even the most diligent person can fall victim when living conditions facilitate rapid spread. Addressing scabies effectively requires policy‑level interventions alongside personal measures.

Ted G

Don’t be fooled by the mainstream narrative; the real agenda behind scabies campaigns is to distract us from larger biometric surveillance programs. Those “prescription scabicides” are often laced with tracking molecules, enabling hidden monitoring of populations. Wake up and question who truly benefits from these so‑called public health efforts.

Miriam Bresticker

Thiss article rreally reminds me of my bout wth scabies last yeaer 😅😅 the mitez were like ninjas! but the tips r solid especially washng everything in hot water 🔥🔥

Claire Willett

Validate: hygiene protocol adherence = mitigation efficacy

olivia guerrero

Wow, what a fantastic read! The depth of detail is simply amazing, and the practical advice is absolutely spot‑on! Kudos to the author for shedding light on a topic that often flies under the radar, especially in community health settings! Keep up the great work!

Dominique Jacobs

Let me break this down for everyone who might have skimmed past the initial sections: the Sarcoptes scabiei life cycle is not just a series of biological steps, it’s a testament to evolutionary efficiency that humans have unfortunately become a host for. First, the adult female burrows into the stratum corneum and lays eggs; that alone shows a level of precision we rarely see in other parasites. The eggs hatch within three to four days, releasing larvae that migrate to the surface – a strategic move to maximize contact with the external environment. Those larvae then molt into protonymphs and later tritonymphs, each stage designed to adapt to specific niches on the skin. By the time they reach adulthood, they’re fully equipped to reproduce, completing the cycle in roughly ten to seventeen days.

Now, consider the public health implications: a single infested individual can seed an outbreak in a crowded setting within days, especially if hygiene practices are lax. Direct skin‑to‑skin contact is the primary transmission route, but remember, the mites can survive up to seventy‑two hours off‑host, turning contaminated bedding or clothing into silent vectors. This is why thorough laundering at temperatures exceeding fifty degrees Celsius is non‑negotiable.

Diagnostically, skin scrapings examined under a microscope remain the gold standard, but clinicians should also be aware of the characteristic burrow patterns and nocturnal pruritus that distinguish scabies from other dermatoses. Treatment protocols typically involve topical scabicides applied from neck to toe, with a repeat dose after one week to ensure any newly hatched mites are eradicated. Oral ivermectin offers an alternative, especially in institutional outbreaks where compliance is a challenge.

Prevention goes beyond individual actions; it demands coordinated public health responses, including contact tracing, mass prophylaxis in outbreak hotspots, and education campaigns that destigmatize the condition. In settings like prisons, shelters, or schools, rapid response teams can dramatically curb transmission.

Finally, let’s not overlook secondary bacterial infections that often follow intense scratching; these can lead to complications like impetigo or even cellulitis, requiring antibiotic therapy. In sum, understanding the life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei equips us with the knowledge to intervene at multiple stages – from personal hygiene to community‑wide measures – and ultimately reduces the burden of this highly contagious disease.