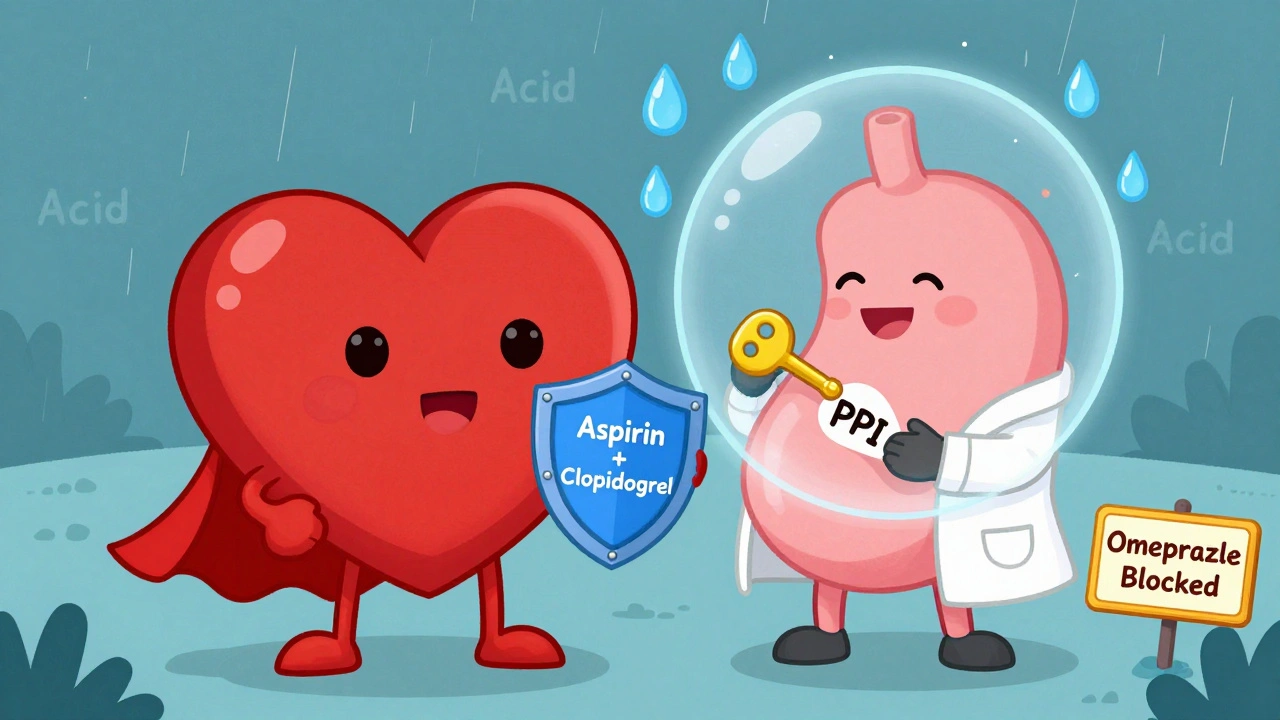

When you're on dual antiplatelet therapy - usually aspirin plus clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor - your blood doesn't clot as easily. That's good for preventing heart attacks and strokes. But it comes with a serious downside: your stomach lining becomes more vulnerable. Every year, tens of thousands of people on these medications suffer gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Many of these cases are preventable. The solution? Adding a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). But not all PPIs are created equal, and using them the wrong way can do more harm than good.

Why GI Bleeding Is a Real Threat on Antiplatelets

Aspirin alone can double your risk of a stomach bleed. When you add a second antiplatelet like clopidogrel, that risk jumps by 30% to 50% in the first month. This isn't theoretical. In a 2025 study of nearly 97,000 stroke patients in Korea, over 300 major GI bleeds occurred within a year - and most happened within the first 30 days of starting treatment. These aren't minor issues. GI bleeding can lead to hospitalization, blood transfusions, and even death.The problem isn't just the drugs themselves. It's how they interact with your stomach. Antiplatelets reduce the protective mucus layer and make blood vessels in the stomach lining more fragile. At the same time, stomach acid keeps eating away at the damaged tissue. That's where PPIs come in - they shut down acid production, giving your stomach a chance to heal.

How PPIs Work - And Why They're So Effective

Proton pump inhibitors like omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole work by blocking the final step of acid production in your stomach. They don't just reduce acid - they cut it by 70% to 98%. That’s powerful. Studies show that when you add a PPI to your antiplatelet regimen, you cut your risk of a major GI bleed by 34% to 37%. In the landmark COGENT trial, this meant one major bleed was prevented for every 71 patients treated over six months.But here's the catch: not every PPI works the same way with every antiplatelet drug. The interaction between omeprazole and clopidogrel is well-documented. Omeprazole blocks an enzyme called CYP2C19, which your body needs to turn clopidogrel into its active form. This can reduce clopidogrel’s effectiveness by up to 30%. In some studies, that translated to a 27% higher risk of heart attack or stroke.

Which PPI Should You Take? Not All Are Equal

If you're on clopidogrel, avoid omeprazole. It’s the most effective at reducing acid - but also the most likely to interfere with your heart medication. Instead, go with pantoprazole or esomeprazole. Both have minimal impact on CYP2C19. In fact, pantoprazole reduces clopidogrel’s effect by less than 15%, and esomeprazole barely affects it at all.Here’s a simple guide:

- On clopidogrel? Use pantoprazole 40 mg daily or esomeprazole 40 mg daily.

- On prasugrel or ticagrelor? You can safely use any PPI - including omeprazole. These drugs don’t rely on CYP2C19, so there’s no interaction.

- On aspirin alone? Still consider a PPI if you’re over 65, have a history of ulcers, or take NSAIDs or steroids.

And don’t confuse PPIs with H2 blockers like famotidine. They’re weaker. A 2017 meta-analysis found PPIs cut GI bleeding risk by 60%, while H2 blockers only cut it by 30%. If you’re at risk, go with the stronger option.

Who Really Needs a PPI? Risk Matters

You don’t need a PPI just because you’re on antiplatelets. The guidelines are clear: only use it if you’re at higher risk. The European Society of Cardiology defines high risk as having two or more of these factors:- Age 65 or older

- History of stomach ulcer or GI bleed

- Taking anticoagulants (like warfarin or apixaban)

- Using NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen) or corticosteroids

If you don’t have any of these, the risks of long-term PPI use might outweigh the benefits. PPIs can increase your chance of C. difficile infection by 0.5%, raise your risk of pneumonia by 0.8%, and may even contribute to chronic kidney disease over time. A 2022 study found that 35% to 45% of PPI prescriptions in heart patients were unnecessary.

On the flip side, a 2025 Korean study showed that even low-risk patients who took a PPI had a 37% lower chance of GI bleeding. That’s significant. But it doesn’t mean everyone should take one. The key is matching the drug to the risk - not giving it out like candy.

When to Start - And How Long to Keep Taking It

Start your PPI on day one of your antiplatelet therapy. Most GI bleeds happen in the first month. Waiting until you have symptoms is too late. You’re not treating a problem - you’re preventing one.How long should you stay on it? For most people, six to 12 months is enough. That’s the typical length of dual antiplatelet therapy after a stent. After that, if you’re still on aspirin alone and have no other risk factors, you can often stop the PPI. But if you’re on long-term aspirin (say, after a heart attack or stroke), and you have one or more risk factors, you may need to stay on it longer. Some newer guidelines now support PPI use for up to 36 months in very high-risk patients.

Don’t just keep taking it forever. Many patients stay on PPIs for years without review. That’s dangerous. Ask your doctor every six months: "Do I still need this?"

The Hidden Problem: Underuse and Overuse

There’s a strange gap in how this works in real life. In Europe, 55% to 65% of heart patients on antiplatelets get a PPI. In the U.S., it’s only 40% to 50%. But here’s the twist: in Korea, only 16.6% of low-risk patients got a PPI - even though the data says they’d benefit.That’s the problem in a nutshell. Some doctors are too cautious. Others are too careless. One cardiologist survey found that 45% of doctors weren’t sure who should get a PPI. Meanwhile, patients often don’t know why they’re taking it. A 2021 study showed 30% of patients were confused about their PPI’s purpose - and many stopped taking it because they feared side effects.

It’s not just about prescribing. It’s about communication. You need to understand why you’re on this combination. If you’re on clopidogrel, you need pantoprazole - not omeprazole. If you’re over 70 and on aspirin, you likely need the PPI. But if you’re 45, healthy, and only on low-dose aspirin? You probably don’t.

What’s Next? New Drugs and Better Tools

The future is getting smarter. A new drug called vonoprazan - a potassium-competitive acid blocker - is coming. It works faster and doesn’t interfere with clopidogrel at all. The FDA is reviewing it as of late 2025. If approved, it could replace PPIs for many patients.Meanwhile, genetic testing is becoming more common. Some people have a gene variant (CYP2C19 loss-of-function) that makes clopidogrel less effective. These patients might need a different antiplatelet - or a different PPI. By 2027, doctors may use blood tests to guide which PPI you get, based on your genes.

And hospitals are finally starting to use decision-support tools. About 78% of U.S. hospitals now have electronic alerts that suggest a PPI when someone is prescribed DAPT. But only 42% of those systems actually check your risk factors before recommending it. That’s like having a GPS that tells you to turn left - even if you’re in the middle of a lake.

Bottom Line: Smart Use Saves Lives

Proton pump inhibitors aren’t magic pills. But when used correctly, they’re one of the most effective ways to prevent life-threatening GI bleeding in heart patients. The key is matching the right PPI to the right patient at the right time.If you’re on dual antiplatelet therapy:

- Ask your doctor: "Am I at risk for GI bleeding?"

- If yes, ask: "Which PPI should I take?" - and why?

- If you’re on clopidogrel, avoid omeprazole. Use pantoprazole or esomeprazole.

- Don’t take it longer than needed. Review it every 6 months.

- Don’t stop it without talking to your doctor - especially in the first 30 days.

This isn’t about taking more pills. It’s about taking the right ones - and knowing why.

Can I take omeprazole with clopidogrel?

No, it’s not recommended. Omeprazole blocks the enzyme (CYP2C19) your body needs to activate clopidogrel. This can reduce its effectiveness by up to 30%, raising your risk of heart attack or stroke. Use pantoprazole or esomeprazole instead if you’re on clopidogrel.

Do all heart patients need a PPI with aspirin?

No. Only patients with risk factors - like age over 65, history of ulcers, or use of NSAIDs or anticoagulants - should take a PPI. For healthy, low-risk patients, the risks of long-term PPI use (like kidney issues or infections) may outweigh the benefits.

How long should I take a PPI with antiplatelets?

Most people take it for 6 to 12 months - the standard length of dual antiplatelet therapy after a stent. If you’re still on aspirin long-term and have risk factors, your doctor may recommend continuing. But never take it indefinitely without review. Reassess every 6 months.

Are PPIs safe for long-term use?

Long-term use carries risks: increased chance of C. difficile infection, pneumonia, and possibly chronic kidney disease. The FDA also warns about bone fractures with high-dose, long-term use. But for high-risk patients on antiplatelets, the benefit of preventing a GI bleed usually outweighs these risks - if used only as long as needed.

Can I use famotidine instead of a PPI?

Famotidine (an H2 blocker) reduces stomach acid, but not as well as PPIs. Studies show PPIs cut GI bleeding risk by 60%, while H2 blockers only cut it by 30%. For patients at real risk, PPIs are the clear choice. H2 blockers are not a reliable substitute.

What if I’m on ticagrelor or prasugrel instead of clopidogrel?

You can safely use any PPI, including omeprazole. Ticagrelor and prasugrel don’t rely on the CYP2C19 enzyme to work, so there’s no interaction with PPIs. You can choose based on cost, availability, or doctor preference.

15 Comments

val kendra

I've been on clopidogrel for 2 years after my stent and was on omeprazole until my pharmacist flagged the interaction. Switched to pantoprazole and haven't had a single stomach issue since. Seriously, if you're on clopidogrel, don't gamble with omeprazole. It's not worth it.

Karl Barrett

The CYP2C19 pharmacogenomic interaction is one of the most clinically significant in cardiology. Omeprazole's competitive inhibition of the enzyme reduces clopidogrel's active metabolite formation by up to 50% in poor metabolizers. This isn't theoretical-it's pharmacokinetics in action. We need to move toward genotype-guided prescribing, not population-level heuristics. The data is unequivocal.

Libby Rees

I'm 68 and on aspirin only. My doctor said I don't need a PPI. I was skeptical but followed the guidelines. No stomach issues in 18 months. Sometimes less is more.

Ben Choy

I've been on pantoprazole for 3 years with ticagrelor and honestly? I feel better. My acid reflux is gone. But I do worry about the long-term kidney stuff. Maybe I should cut back? Anyone else feel like they're on too many pills?

Bill Wolfe

Honestly, if you're taking PPIs long-term, you're just trading one problem for another. The C. diff risk alone should make you think twice. And don't get me started on the bone density loss. People are just popping these like candy because some doctor told them to. It's lazy medicine. You want to prevent bleeding? Eat less spicy food. Don't take NSAIDs. Stop smoking. But nooo, let's just chemically shut down your stomach. Pathetic.

Jake Deeds

I'm a nurse. I've seen three patients in the ER this year with GI bleeds from DAPT + omeprazole. One died. I don't care what the guidelines say-if you're on clopidogrel, you avoid omeprazole like the plague. It's not even a debate anymore. If your doctor prescribes it, get a second opinion. This isn't just medical advice-it's survival.

Alex Piddington

I appreciate the depth of this post. As a physician, I’ve seen the gap between evidence and practice. Many patients don't understand why they're on a PPI, and many providers don't know the nuances of CYP2C19 interactions. Education is the missing link. We need better patient handouts and EMR prompts that flag high-risk combinations.

George Graham

My dad had a heart attack last year. He was on clopidogrel and omeprazole for 6 months before his GI bleed. He was hospitalized for 11 days. We switched to esomeprazole and he's been fine since. I wish we’d known this sooner. Please, if you're reading this and you're on clopidogrel-double check your PPI. It could save your life.

Shofner Lehto

The real issue isn't the drugs-it's the system. Doctors are rushed. Patients don't ask questions. Pharmacies don't always flag interactions. We need automated alerts tied to genetic data, not just a checkbox. Until then, patients need to be their own advocates. Know your meds. Know your risks.

Dematteo Lasonya

I was on omeprazole with clopidogrel for 4 months. My GI doc called me out on it. Said I was lucky I didn't bleed. Switched to pantoprazole. No more burning. No more fear. Simple fix. Why isn't this common knowledge?

Rudy Van den Boogaert

I'm 52, healthy, on aspirin only. My doc said no PPI. I didn't ask why. Now I'm glad I didn't take it. I don't want to be on meds I don't need. Sometimes the best treatment is not taking anything.

Chad Handy

I've been on PPIs for 8 years. I have chronic kidney disease now. I don't know if it's from the PPIs or my hypertension or both. But I do know I took them without question because my cardiologist said it was "safe." I feel betrayed. I'm not mad at the doctor-I'm mad at the system that lets this happen. People need to be warned. Not just told.

Rebecca Braatz

STOP waiting for symptoms! Start the PPI on day one. If you wait until you're bleeding, it's too late. I've been in the ER too many times to count. Prevention isn't optional. It's non-negotiable for high-risk patients. Don't be the person who says "I didn't know." You know now.

Emmanuel Peter

So let me get this straight. You're telling me that after spending $20,000 on a stent, the next thing you do is take a $5 pill that might cause kidney failure? And you're okay with that? I'm just saying-maybe we should be looking at better antiplatelets instead of patching the side effects with acid blockers. This feels like a bandaid on a gunshot wound.

michael booth

The data is clear: appropriate PPI use reduces GI bleeding by 35%. The data is also clear: inappropriate use increases risk of infection and renal injury. The solution is not to eliminate PPIs, but to implement structured risk assessment and time-limited prescribing. Every patient should have a documented indication, a review date, and an exit strategy. This is standard of care. Let's start acting like it.