When someone starts taking opioids for chronic pain, they often expect relief from physical discomfort. But many don’t realize that opioids can also change how they feel emotionally-sometimes in ways that are hard to notice until it’s too late. Between 13% and 54% of people on long-term opioid therapy develop depression, and in many cases, it’s not clear whether the depression came first or was triggered by the medication. This isn’t just a side effect-it’s a cycle that can trap people in worsening pain and deeper low moods.

How Opioids Can Make You Feel Worse, Not Better

Opioids work by binding to receptors in your brain that control pain, but they also affect areas tied to emotion and reward. In the short term, this can feel like relief-not just from pain, but from emotional heaviness too. Some people report feeling calmer or even euphoric after their first dose. That’s because opioids activate the same brain pathways that natural pleasure chemicals like endorphins do. Preclinical studies show that drugs like morphine and buprenorphine reduce signs of despair in animals, mimicking antidepressant effects.

But here’s the catch: what works short-term often backfires long-term. When opioids are used for weeks or months, the brain adapts. It produces fewer of its own natural pain and mood regulators. The system becomes dependent on the drug just to feel normal. Over time, this leads to emotional numbness, loss of interest in things you used to enjoy, and persistent sadness-even when the original pain is under control. A 2016 study of burn patients found that the more opioids someone received over time, the higher their depression scores became. For every 50 mg increase in daily morphine equivalent dose, the risk of depression nearly tripled.

The Chicken-or-Egg Problem: Pain Leads to Depression-or Vice Versa?

It’s easy to assume that chronic pain causes depression. And yes, living with constant discomfort can wear anyone down. But research shows it’s not that simple. People with depression are more likely to develop chronic pain, and they’re also more likely to be prescribed opioids. One large study found that depressed patients were twice as likely to move from short-term to long-term opioid use compared to those without depression. And once they’re on opioids long-term, their depression gets worse.

Genetic studies help untangle this. A 2020 study using DNA data from over 300,000 people found that people genetically predisposed to using prescription opioids were also more likely to develop major depressive disorder. That suggests opioid use itself may be a direct contributor to depression-not just a side effect of pain. This isn’t just correlation. It’s evidence of causation.

Meanwhile, some patients are being prescribed opioids to treat what looks like pain but is actually emotional suffering. Depression can make physical pain feel more intense. A person might say, “My back hurts all the time,” when what they really mean is, “I can’t get out of bed. I don’t care about anything anymore.” Without proper screening, doctors may treat the symptom (pain) instead of the root cause (depression).

How to Spot Depression Early When You’re on Opioids

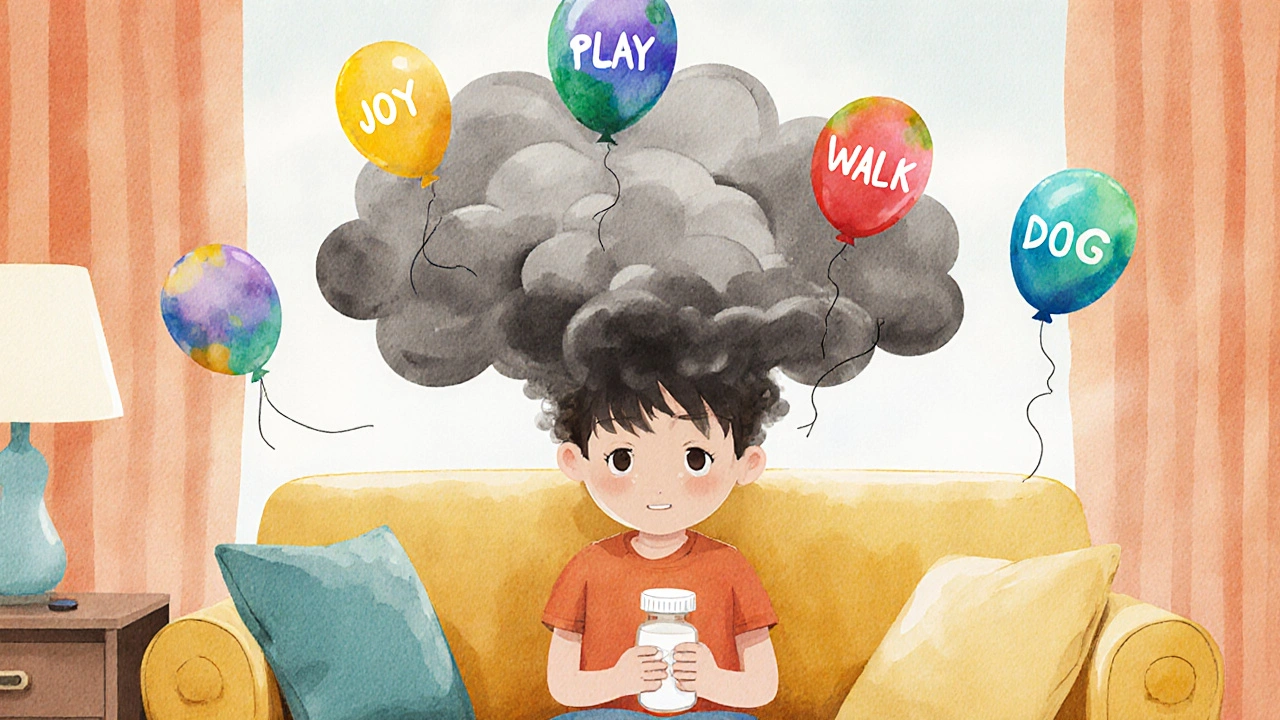

Depression doesn’t always show up as crying or saying, “I’m sad.” On opioids, it often looks like:

- Feeling emotionally flat-even when good things happen

- Loss of motivation to do things you used to enjoy

- Sleeping too much or too little, even when pain isn’t worse

- Feeling hopeless about recovery or the future

- Increased irritability or anger out of nowhere

These signs can be easy to miss. Many assume it’s just the pain acting up or the medication making them “tired.” But these aren’t normal side effects-they’re red flags.

Doctors should be screening for depression regularly, especially in people on long-term opioids. Tools like the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) are simple, free, and reliable. It asks nine questions about mood, sleep, energy, and thoughts of worthlessness. A score of 10 or higher suggests moderate to severe depression. Yet, only about 40% of primary care doctors routinely screen for depression before starting opioids, and even fewer do it regularly after.

What to Do If You Notice Mood Changes

If you’re on opioids and feel your mood slipping, don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s just “how things are now.” Talk to your doctor. Bring up specific changes: “I used to love walking the dog. Now I don’t even want to get up.” Or, “I cry for no reason, and I can’t shake this heaviness.”

There are options. One of the most promising is buprenorphine, a medication used for opioid addiction that also has antidepressant properties. In studies, patients on buprenorphine maintenance therapy saw their depression scores drop from severe to mild within three months. Low doses (1-2 mg/day) have even shown rapid antidepressant effects in people who didn’t respond to traditional antidepressants. The catch? The FDA hasn’t approved it for depression yet, so doctors can’t prescribe it officially for that purpose-even though the science supports it.

Another path is combining pain management with therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to cut opioid use by 32% in chronic pain patients by helping them reframe pain and build coping skills. When depression is treated, pain often gets easier to manage too.

Breaking the Cycle: Treatment That Addresses Both

The biggest mistake is treating pain and depression separately. You can’t fix one without the other. If you’re on opioids and depressed, you need a plan that tackles both. That means:

- Regular mood checks (at least every 3 months, or monthly if you’re new to opioids)

- Open conversations with your doctor about emotional changes

- Exploring non-opioid pain options: physical therapy, acupuncture, nerve blocks

- Considering antidepressants that work well with pain, like SNRIs (duloxetine, venlafaxine)

- Getting therapy-especially CBT or acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)

Some people worry that reducing opioids will make their pain worse. But studies show that when depression improves, pain tolerance improves too. People often need less medication overall. One trial found that patients who received CBT alongside pain management reduced their daily opioid dose by an average of 32%-without worsening pain.

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Researchers are working hard to understand why opioids cause depression in some people but not others. The National Institutes of Health just funded a $4.2 million project using brain scans to see how opioid use changes mood circuits over time. Another study tracking 5,000 people with chronic pain and depression will follow them until 2026 to map out exactly when and how depression develops.

These studies are critical. Right now, doctors are flying blind. They know opioids can cause depression, but they don’t know who’s most at risk or how to stop it before it starts. Until we have better tools, the best defense is awareness.

Final Thoughts: You’re Not Alone, and It’s Not Your Fault

If you’re on opioids and feeling down, it’s not weakness. It’s biology. The brain changes under long-term opioid exposure, and that can pull you into depression-even if you never had it before. The good news? You can get out. With the right support, mood can improve. Pain can be managed differently. And you don’t have to go through it alone.

Start by asking your doctor: “Could my mood changes be linked to my medication?” Then ask: “What else can we try?” The goal isn’t to stop opioids overnight. It’s to find a balance-where pain is managed without sacrificing your mental health.

Can opioids cause depression even if I don’t misuse them?

Yes. Even when taken exactly as prescribed, long-term opioid use can lead to depression. Studies show that people using opioids for chronic pain have a significantly higher risk of developing major depressive disorder, especially with daily use or doses above 50 mg morphine equivalent. This happens because the brain adapts to the drug, reducing its natural ability to regulate mood.

How often should I be screened for depression if I’m on opioids?

Experts recommend screening at the start of opioid therapy, then every 3 months. If you’re new to opioids or have a history of depression, monthly screening for the first 6 months is advised. Tools like the PHQ-9 take less than 5 minutes and can catch early warning signs before they become severe.

Is buprenorphine a good option if I’m depressed and on opioids?

Buprenorphine is one of the few opioids that may actually help with depression symptoms. Studies show it reduces depressive symptoms in people with opioid use disorder and chronic pain, even at low doses. While it’s not FDA-approved for depression, many doctors use it off-label when other treatments haven’t worked. It’s worth discussing if you’re struggling with mood changes while on opioids.

Can treating depression reduce my need for opioids?

Yes. When depression improves, pain often becomes more manageable. One study found that patients who received cognitive behavioral therapy alongside pain treatment reduced their opioid doses by 32% without worsening pain. Treating the mind helps the body heal too.

What should I do if my doctor won’t screen me for depression?

Take the initiative. Print out the PHQ-9 questionnaire from a trusted source like the American Psychiatric Association and bring it to your appointment. Say, “I’ve been feeling off lately, and I’d like to check if this could be depression. Can we go over this together?” Many doctors will respond positively when patients lead with data and clear concerns.

9 Comments

Katelyn Sykes

Opioids messing with your mood isn't some rare glitch-it's built into the biology. I've seen it in my dad. He took them for back pain, thought he was just tired, then one day he couldn't even watch his grandkid's soccer game. No crying, no ranting-just gone. That emotional flatline? That's the drug, not him.

Gabe Solack

Big respect to the author for calling out buprenorphine as an off-label option. 🙌 I'm on 1.5mg daily for chronic pain and honestly? My depression lifted faster than the pain did. Docs won't admit it, but this isn't just for addiction-it's a mood stabilizer with fewer side effects than SSRIs. If you're stuck in this loop, ask for it. No shame.

Bailey Sheppard

This is the kind of post that should be mandatory reading for anyone prescribed opioids. Not just patients-but doctors too. The fact that only 40% screen for depression before starting treatment is terrifying. We're treating symptoms, not people. I'm glad someone's putting this out there clearly.

Kristi Joy

For anyone feeling lost right now: you're not broken. Your brain isn't failing you-it's adapting to a chemical it wasn't meant to live with. That doesn't mean you're weak. It means your body tried to protect you, and now it needs help rewiring. Therapy, low-dose buprenorphine, movement-even small walks-can rebuild that connection. You don't have to do it alone.

Hal Nicholas

Of course opioids cause depression. You're literally hijacking your brain's reward system with a synthetic high. It's like replacing sunlight with a flashlight and then wondering why you're depressed. This isn't medicine-it's emotional anesthesia. And now we're surprised when people fall apart?

Shaun Barratt

The data presented here is methodologically sound and aligns with recent meta-analyses from the Journal of Pain Medicine (2022) and the NEJM review on neuroplasticity in chronic opioid exposure. The PHQ-9 remains the gold standard for longitudinal screening, and the 32% reduction in opioid dosage observed in CBT cohorts is statistically significant (p < 0.01). I would recommend cross-referencing with the NIH-funded fMRI study on mu-opioid receptor downregulation in the prefrontal cortex, which provides neuroanatomical validation of the behavioral observations.

Yash Nair

USA is full of weak people who cant handle pain so they take drugs. In India we work through pain. Depression? That's for people who sit on couches all day. Get up. Move. Stop blaming medicine. Your mind is weak not the drug.

Louie Amour

Of course the government doesn't want you to know buprenorphine works for depression. They'd rather keep you on SSRIs and oxycontin so Big Pharma can keep milking you. This is why I don't trust doctors-they're paid to keep you dependent. Read the papers yourself. Don't let them gaslight you into thinking your suffering is normal.

Girish Pai

Neuroadaptation via mu-opioid receptor internalization triggers downstream dysregulation of the HPA axis and monoaminergic pathways, particularly serotonergic and noradrenergic tone, which directly modulates affective processing in the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex. This neurochemical cascade is quantitatively dose-dependent and temporally persistent, with longitudinal biomarker studies confirming elevated IL-6 and cortisol levels correlating with PHQ-9 escalation. Hence, the clinical imperative for multimodal intervention is not merely therapeutic-it's neurobiologically deterministic.